In the mid-late 1970s, Judy Chicago (with 400 unnamed assistants) worked on The Dinner Party and provoked (among other, more structurally concerned criticism) questions about the representation of women. Do we want, politically, personally, pleasurably, to see an individual woman represented by a symbolic image of her genitals? Chadwick’s Meat Abstracts totally removed from Chicago’s work in production, intent and effect-provoke questions central to the late 80’s debate around the representation of desire. How does the mapping of the female body cope with its specificity, its orifices which are neither internal nor external? Are there visual languages of femaleness or femininity? Can we (should we aim to) represent the female body, provoke female desire, without evoking the Freudian and Lacanian axis of loss, of wounding? Does the woman’s body inevitably evoke lack and therefore represent in and of itself, desire? Underlying these questions are others concerning the economy and politics of meat-eating; and the evocation and projection of desire onto cut and dead meat. Also foregrounded is the cult in certain intellectual circles of the pornographic writings (utterly non-beneficial to women) of people like Georges Bataille, where sexual pleasure goes hand in hand with the manipulation and victimisation of the Other, with psychic and physical damage, and death, preferably at the point of orgasm.

Where Chadwick’s work has been so powerful, particularly the Meat Abstracts and Of Mutability, is that it makes no attempt to side-step the asking of any of these questions, and does not polemically provide answers. Instead, with complete candour and lack of timidity, she goes straight for the centre of the most difficult areas (politically, psychically, in representation) of the debate, and re-faces us with them. The ambiguity of her own positioning is veiled by the confidence of her means of production; it is the point at which she appears to be most vulnerable, and where questions about her intent (rather than the effect) become pertinent. This was particularly so in Of Mutability, an audacious attempt at mapping female pleasure at its plenitude, inscribed on the female body, carried out on a vast physical, emotional and intellectual level. Looking back at the work in Enfleshings, it still strikes me that Chadwick in some cases tried to use some images as metaphor for one thing when their stronger signification is of things or events quite opposite to those she intended.

There are two obvious examples of this. The first concerns Chadwick’s use of her own body. Would she have been as willing to use her body in the piece had she not been so neatly proportioned, or if she had been older? Marina Warner’s essay quotes her as saying that the photocopies are assembled in a “long-limbed, healthy, idealised” form. Whose ideal, and why? This is a question that the new women’s movement has been asking of images of women since it started, and they are not questions to be avoided because the artist is a woman. How does this particular ideal help carry the meaning of the work, or is it a hindrance?

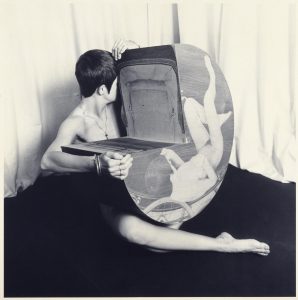

The other problems are with the objects around the figures. Two figures have been blind-folded, one with a silken scarf, one with an improvised hood. This cannot work as a metaphor for the blindness of extreme passion or ecstasy when the immediate signification for most women will be the powerless ness of inflicted sadism. I was reminded very strongly of the sado/masochist images of David Bailey–photographed from the viewpoint of the sadist, a woman in the role of the masochist. And again, the sensations evoked by the ‘cornucopia’ figure are of hanging, of vomiting, of death, of claustrophobia, of bondage–not of the plenitude of pleasure; the face of the image looks violently dead; the rope from neck to foot, pulling the body in an arc, implies a fascistic form of external control rather than the pleasurable tension of muscle pulling against muscle and limb pushing against limb.

However, the device of the pool into which the viewer looked to see these images and their companions meant that the boundaries between subject and object were significantly blurred: was one looking at the body and pleasure of another, or, like Narcissus, captivated by the sight of oneself? Was pleasure projected outside the self onto the body of the other?

What I think Chadwick allowed the woman viewer to do when looking at Of Mutability was to be in a constant state of pleasurable flux, slipping between being the desired object and the desiring subject. Which is precisely why, when there are images in the pool that signify something other than potential pleasure, there is such an acute jarring. There is no room in the pleasure garden for a damaged, or damaging, narcissism.

Where To Buy Paintings In Singapore

The problem is to find metaphors and equivalents that are not already pre-determined, or that can successfully be appropriated. Looking through Enfleshings it becomes clear that this is a central concern of Chadwick’s.

Her latest work, Viral Landscapes continues this quest. Photographs of a rocky coastline are superimposed with histological photographs of cells from Chadwick’s body; a swatch of colour down the left hand side of each (and, to an extent, the configuration of the landscape) hints at the origin of the cells represented–blood, throat, ear, cervix and lymph from a shingle sore. ‘Viral’ interference is provided on the landscape photographs by paint. In prospect, in the reproductions, the work looked engrossing. Notions of the dispersal and colonisation of the body by the virus and of the land by the body seemed to the fore.

The installation as it was at Oxford seemed to let down this fruitful potential. The five photographs, (each some ten feet long and four feet high) were ranged frieze-like along one wall of a gallery. For the first time in one of Chadwick’s exhibitions I did not experience in any significant way a bodily interaction and exchange with the work–despite the fact that the walls had been painted an acid yellow. The viewer was thrown back, remained external to the piece, which was ironic, given its concerns. The potential richness of allusion, the stunning significance of AIDS to all of us, somehow got lost in the unsympathetic shape of the gallery.

Chadwick’s work has been amongst the most significant in the past decade, and with the publication of Enfleshings it is as if she has ‘come of age’ as an artist. I assume that the work she has begun in Viral Landscapes is going to develop in as provocative a form as her work of the 80s. Her work to date has always been ‘difficult’, has always left the viewer on her side, yet with some critical distance. Viral Landscapes as shown at Oxford did not seem resolved or confident enough to allow this. Almost as if Chadwick herself has been so far dispersed this year that the coastline images have been more appropriate to her than to the viewer. She has not been able to infuse them with the intimacy suggested by the cells. However, it is an area rich for working in, and I anticipate her next show with much pleasure.